Short description of Individual Emission Rights for Flying (IERF)

070825

Background

- To avert even greater climate disasters consumption of fossil energy must be curtailled quickly and decisively.

- Aviation is a fossil sector that is growing rapidly and cannot be made sustainable in the timeframe required.

-

The consumption and investment patterns of a relatively small group of the population directly or indirectly contribute disproportionately to greenhouse gases (Chancel et al., 2023).

Flying is an outstanding example of this phenomenon.

Method

Since 2019 I have been working on a method that has the following goals:

- to reduce global warming by limiting flying for leisure purposes;

- to generate revenues and transfer those to sustainable mobility, by train, bus; also invest part of those revenues in sustainable energy projects in countries that do not emit a lot but that are suffering from climate damage;

- promote social justice by giving citizens equal emission rights that they can buy or sell, and by rewarding citizens who do not emit CO2 by flying;

- to avoid shortcomings of existing tax measures such as EU ETS, Corsia and individual flying tax;

- to involve citizens in quantifying the variables of the method, by making their values explicit;

- to promote broad awareness of the danger of climate change, of biodiversity loss and of the link between CO2-emissions and social inequality of citizens within one's own country and between countries.

After describing the method, I will show how the method works out financially based on realistic individual flight data. Further, I will reference four studies with outcomes that inspire optimism about the acceptance of the method.

Description

In my plan, a government agency gives every citizen from the age of 18 rights to fly every year. The rights relate to traveling a certain distance. (Distance is very stongly correlated with emission). I propose a distance of 5000 kilometers. I call such rights Individual Emissions Rights for Flying (IERF).

Preferably, several countries, for example of the European Economic Area, are involved in a IERF-plan. However, in order to speed up climate mitigation, an individual country could feel the urgency and could have the moral courage to take the initiative.

An IERF app will be developed. This digital app arranges the sale and purchase of IERFs by citizens and keeps a database of citizens air travel data.

Citizens are informed about the availability of their IERF via an app for confidential data exchange between government and citizens (in the Netherlands we have an app called DIGID, in the European context there is eIDAS).

Citizens can access their IERFs by logging in on the IERF-app (my.IERF). Their identity is checked by the data exchange app that is similar with DIGID or eIDAS.

What is the price of an IERF? The calculation of this is partly an empirical, partly a political question. Inputs for the calculation are: how large is the current carbon budget for aviation in the country or countries concerned, what is the severity of the climate damage at that time, what is the expected reduction of the total number of air kilometers thanks to pricing?

Three types of citizens using IERF

We can distinguish:

- Citizens who do not want to fly, do not want to receive a reward and do not want to make their IERFs available to other air passengers. These citizens do not need to take action. Their IERFs will not be added to the reservoir of kilometers (explanation follows later).

- Citizens who do not want to fly and who want to receive a reward for not emitting CO2 (and nitrogen, noise etc). They can sell their IERFs with one click.

Suppose an IERF (of 5000 kilometers) costs 100 euros and each citizen within this category receives 50 euros of that amount The IERF app transfers the 50 euros to the citizen’s bank account.

The 5000 kilometers of the IERF that has beeen sold come into a reservoir of kilometers that is managed by the IERF app. The IERF is removed from the reservoir.

- Citizens who want to fly specify their flight destination.

The IERF-app determines the “distance as the crow flies” in kilometers to that destination. If the distance of travelling back and forth is less than or equal to the distance of the citizens own IERF (in the example 5000 kilometres), no additional IERFs need to be purchased. If the distance is greater than that of his own IERF, a citizen must purchase one or more IERFs that are in the reservoir, i.e. previously sold by other citizens.

The process of selling and buying does not require any kind of interaction between individual citizens.

The IEFR app determines the price for a citizen based on the distance in kilometers, in the example (100 euros for an IERF of 5000 kilometers) 0.02 euros per kilometer. (Later we will discuss the progressive schedule of IERF.)

The citizen deposits the euros for the purchase of kilometers for the wanted trip into the account associated with the IEFR app. The app creates a digital certificate for the citizen to make the trip.

Citizens can purchase flights as long as enough IEFRs are in the reservoir of the IEFR-app.

Extra rules in IERF

Distances in kilometers can be multiplied by a weight greater than 1 when nearby destinations are concerned that can be easily reached by train (for example Amsterdam-Paris) and when business class is chosen corresponding with much more space, thus emission, than economy class. The IERF app collects this additional information and computes the resulting distance measure in kilometers.

For reasons explained later we propose to install a progressive function between prize and number of kilometers in the IERF-app so that a citizen who travels far away and frequently will have to pay prices that become gradually higher than 0.02 euro per kilometer.

Other characteristics

The validity period of IERFs and the refund of euros for unused certificates have been considered in my approach.

Diverse functions of the IERF-app, related with individual, private or with general, public information, are described elsewhere.

Buying a ticket

Ticket sites of airlines that are flying to and from the country or countries where IERF has been introduced must be somewhat adapted.

Such a ticket site must do four things:

- When the citizen lives in a IERF-residency, check that the intended trip on the ticket site – destination, forth or/and back, comfort class - corresponds to the certificate of the IERF app.

- Provide information to citizens about the result of the match. Cancel the purchase, when the match is absent.

- After purchasing the ticket: inform the IERF app that the purchase has been successful.

- Add a code to the ticket indicating that the match is OK.

Perhaps this procedure can be made even simpler, preferably without burdening airports with this.

Check at the airport

At the airport on the day of departure, it must be checked whether tickets of passengers from the country/countries with IERFs have the necessary (QR)code printed on it.

Complications

Of course, there are problems associated with IERF, due to its complexity and the variety of interests involved. For instance:

- Cancellation of a trip.

- Double passports.

- Evasive behavior, for example: by car or train to Brussels, or by plane to Reykjavik, and from there with a ticket without IERF to another destination further away.

- Younger people (18-35) are the most eager flyers. Although the urge of young people to meet new countries, cultures and people is quite understandable this poses a difficult problem for IERF.

- Citizens from migration countries who want to visit their families.

Empirical evidence for IERF

We were allowed to use an empirical database from the Kennisinstituut voor Mobiliteitsbeleid KiM (Knowledge Institute for Mobility Policy) in the Netherlands (KiM, 2024). Data on annual flying behavior of 4,000 Dutch citizens aged 18 to 80 were collected. We used the summed flight distances.

Half of the respondents do not fly. In line with other research on inequality of consumption (Chancel et al., 2023), the recorded distances of flyers are extremely skewed. Very many people cover relatively short distances (less than 5000 kms) and very few people cover extremely long distances.

For detailed results, I refer to this page.

Distribution of distances and of revenues of IERF

To account for the skewed distribution of flown kilometers and emitted CO2, I devised a progressive scheme for IERF that ranges from 0.02 to 0.06 euros per kilometer. The distribution of distances is divided into five classes (brackets) that do not represent equal proportions of the sample.

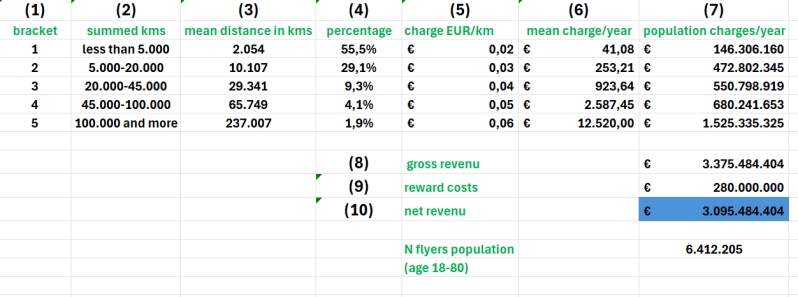

Table 1 below provides insight into:

- Mean flown distances in the five brackets of distance. 55,5 per cent of the citizens flew less than 5.000 kms with a mean distance of 2000 kms whereas 1,9 per cent flew more than 100.000 kms with a mean of 237.000 (!) kms. (The data also revealed that half of the summed kilometers was consumed by only 5,4% of the flyers.

- Method of calculating the charge; with this scheme, a citizen who flies 150,000 kilometers in a year will be charged with : (5,000*0,02) + (15,000*0,03)+(25,000*0,04)+(55,000*0,05)+(50,000*0,06) = 7300 EUR.

When it comes to three flights of each 50,000 kilometers, the charge on those flights becomes increasingly higher: first flight 1800 EUR, second flight 2500 EUR, third flight 3000 EUR.

Table 1. Distribution of kilometers flown annually. Projected revenues from IERF.

The reward costs (9) in the table are based on the guess that 80 per cent of the non-flyers will sell their emission rights and receive 50 EUR in return.

The net revenu of more than three billion EUR is very significant.

For more information about IERF and the KiM-data please see this page.

Some caveats when interpreting these findings are:

- The costs of developing, operating and maintaining the IEV application have not been taken into account.

- Additional costs at the airport of checking whether emission rights have been paid are not included.

- It is expected that the yield of IERF will be lower than shown in the table due to the immediate effect of IERF in saving flown kilometers.

- Not all summed kilometers of the 18-80 year flying citizens in the population can be covered by IERF-certificates, i.e. 67% of 92 billion kilometers. This is however no problem. Arguments: 1. fewer certificates are needed due to the expected savings effect of IERF (see previous point), 2. The government can temporarily offer more purchases of emission rights than are covered by certificates sold.

Acceptance of IERF

I am happy that I have found quadruple support for the IERF approach.

1.

The Social Cultural Planning Office (SCP) in the Netherlands conducted a survey study that is relevant to the acceptance of IERF (April 2024). The results can be found, in Dutch language, on this page.

Dutch citizens are concerned about climate change and they are willing to show more sustainable behavior themselves. This also includes flying less. They do want a clear framework from the government to adapt their behaviors. Contrary to what the government may suspect, “freedom and joy” are not the dominant needs of many Dutch people with climate change underway.

Respondents on the survey fear that if the government continues to act in the area of climate as it has done so far, the financial inequality between rich and poor will increase.

2.

Research by Kennisinstituut voor Mobiliteitsbeleid (KiM) on the sample of flying citizens (2024, 2025) showed that highly educated individuals have the highest climate awareness but also fly the farthest. The researchers believe that the lack of structure (taxing undesired behavior, rewarding desired behavior) by the government is responsible for the failure to implement individual values.

3.

Research agency Ipsos I&O (2025) comes to similar conclusions after studying flying behavior in a sample of 18-24 year citizens in The Netherlands. Ipsos speaks of climate paralysis to characterize the gap between flown kilometers and perceived values.

Based on the above results it is my impression that the Dutch population will accept the IERF approach as meaningful, effective and fair.

4.

Results from a Konstanz-Paris research project on carbon perceptions of 1400 citizens (Köchling et al., 2025) also seem to support the acceptance of IERF.

The vast majority of participants in the survey study, namely 80%, believed that reducing CO2 emissions is necessary.

Participants also noted that emissions are distributed unequally: the wealthier the citizen, the more emissions. This perception aligns with factual data, such as in flying where wealthy citizens accumulate the most flight kilometers.

Conversely, participants believe that wealthier citizens should ideally make the most effort to reduce their emissions. There is thus a gap between values and reality, which was also found in the previously mentioned research by SCP and Ipsos I&O.

The authors reserve the term "carbon perception gap" for another remarkable phenomenon: although particularly wealthy individuals emit more CO2 and also perceive their group that way, they believe that they as individuals emit less than their peers. This phenomenon resembles what KiM also noted: climate awareness is related to education level, yet highly educated individuals tend to fly more.

The authors conclude that the results support the adoption of structural and redistributive climate measures. In the words of the authors: “By making fairness a central element of climate policy communication,governments can foster stronger public endorsement and more effective implementation. “

Discussion

Should the revenu from IERF be reinvested into aviation, as the aviation industry will undoubtedly demand?

My conviction is NO!

Consider the answers to a few questions to understand this conviction.

- Are unsustainable aircraft being dismantled by the airlines?

- Are airlines willing to give up their discount policy for frequent flyers?

- Is the government going to set up wind farms of thousands of square kilometers to provide half of the clean molecules to less than 6% of the flying citizens?

What about business flying?

IERF only relates to private travel by plane. For saving on business flights for companies, I find T&T's approach very useful.

Will the politics dare to implement IERF?

Highly unlikely. The aviation lobby is strong. Right-wing politics is now dominant at the government level in many countries around the world. Those politicians are more afraid of wealthy citizens who believe their freedom is being curtailed than they are of the consequences of climate warming, which they see as an abstract problem. Those consequences are especially harmful to poor citizens in whom those politicians are not interested.

Politics will more likely implement an emergency stop to aviation in the future than start making savings in fossile consumption now.

Still, I hope for the arrival of a government with decisiveness, morality, and courage that will implement IERF.

Flying from airports just across the border

I think that many more people will start to realize the damage caused by flying, including transportation to airports, noise, and emissions of harmful substances other than CO2. They will be able to successfully invoke the climate advice of the International Court of Justice (July 24, 2025) to contest the arrival of masses of Dutch travelers.

Would you be willing to mentally support my proposal?

Thank you in advance for your support by filling out this form!